Introduction

Over the years I’ve developed a system of note taking that has allowed me to learn faster than ever before. It’s made me highly productive, since it helps me to recall complex coding scenarios and to refine techniques that I use every day. It’s also helped speed up the debugging process in certain situations that previously would've taken hours. I would even dare to say this system has helped me significantly decrease the number of times I make the same error twice.

How does this wonderous system work? I’ll show you.

My Short Evolution of Note Taking

I began by jotting down notes in a simple text file. At the time I was using Sublime Text and stored my notes in the root directory of my Dropbox. It worked, but it obviously didn’t scale, and it soon turned into a folder. One folder titled “Coding Notes” housed files on different languages, frameworks, and tools like Ruby on Rails, Javascript, and Heroku. For each project, I used hidden .notes file or simply carved out a section of the Readme for my own gotchas. It was a good start, but I was inconsistent in my note taking practices and only added to the files in batches every so often.

Over time, I realized I didn’t have a great way of categorizing and searching. A professor recommended Evernote, which was free at the time for any number of devices. I started to branch out and add my class notes, recipes, Spanish lessons, job searches, and anything else I was interested in. It helped my learning immensely.

Enter Quiver

It was always apparent to me that Evernote was great for plain text and images but far from a code editor. It took me months of experimenting with various tools on the market, from Bear to OneNote to Google Keep. After three months, I finally found my external brain; Quiver.

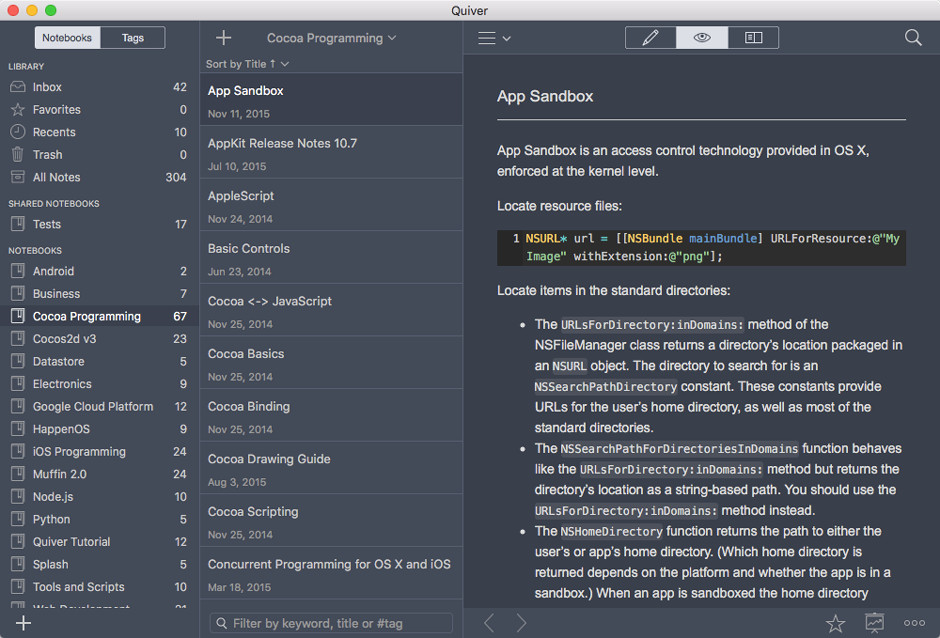

Sample notes and layout in the app

Quiver is a programmer’s best friend (besides Vim and Tmux, of course). It supports markdown, has syntax highlighting for hundreds of languages, saves notes in JSON, has both folders and tags for organizing, optional Vim navigation, and it allows you to view both the raw note text and the presentation of it at the same time. Since finding Quiver, I’ve written exclusively in markdown. It’s insurmountably faster than clicking on a formatting tool or even highlighting and using a shortcut. Combined with Vim navigation and global search, it allows you never to leave the keyboard.

In order to share and backup notes, it’s best to keep the Quiver notebook root in Dropbox, Google Drive, or version control. The migration from Evernote or other tools is a cinch as it has an importer for Evernote .enex files as well as plain text, markdown, or other Quiver notebooks.

How I Use Quiver

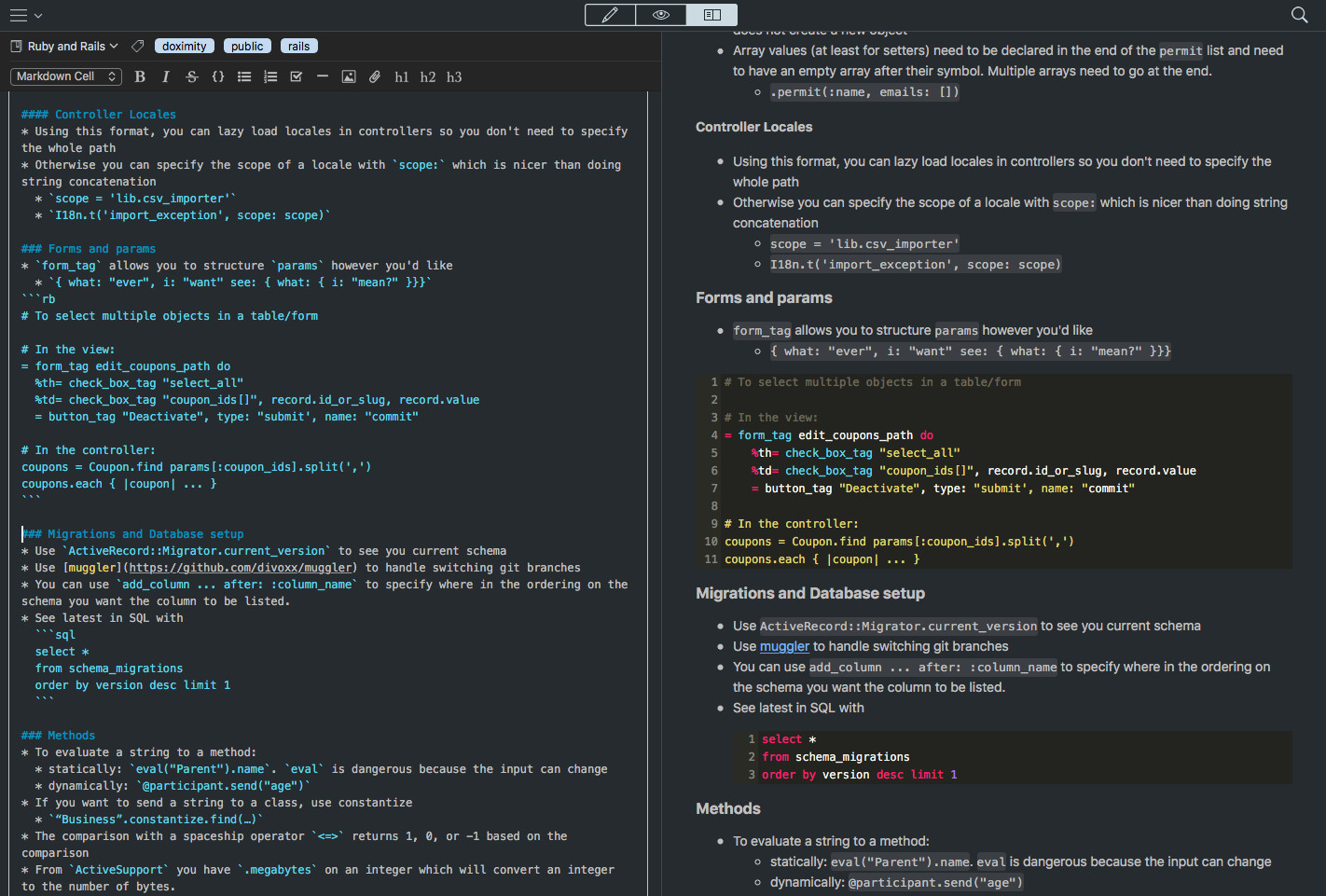

Split screen with both Ruby and SQL syntax highlighted snippets

My notebooks are high-level categories, such as Programming, Cooking, and Work. Quiver allows you to subfolder, however, and it aggregates all content of the children in the parent. I typically don’t store notes in parent folders, just other child folders. In the high-level category of Programming, I have things like Languages & Frameworks, Fundamentals, and Databases. Under Languages & Frameworks, I have Ruby and Rails, and under that I have notes such as Gems, Rails, Testing, and Web Scraping.

Most of my coding note files have the same structure; there is a General heading at the top and a Troubleshooting and Debugging heading at the bottom. The general section contains the most important elements to keep in mind and the most important lessons I’ve learned. This is a section that I read every time I jump back into a language, framework, or tool that I haven’t used in a while.

For example:

- Never touch a line of code without test coverage

- Never use inline

rescuein Ruby - Don’t confuse the jQuery and JS apis for method calls

- Don’t use top-level CONSTANTS in spec files due to namespacing

- Red, Green, Refactor

In my notes, everything is a bullet point. This allows me to nest concepts but also indent code examples to the same level of nesting.

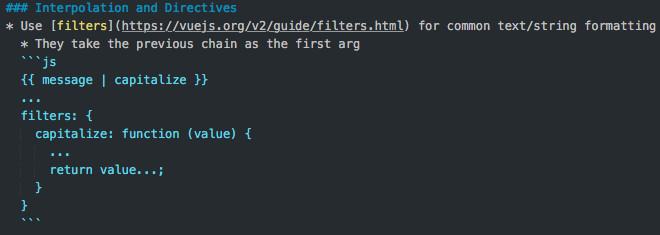

Example from my VueJS notes

I start every header as a ### H3 header so that I can nest in bigger or smaller headings as I go on. When nested bullets get too deep, they deserve their own #### H4 topic. If that gets too big, then it deserves it’s own H3 header, H2, and so on. If the note gets too big, it becomes a folder with notes for all the major topics. For example, my Ruby on Rails note became a Ruby and Rails folder with notes: Ruby, Rails, Rails Testing, Gems, GraphQL, RubyMotion, Troubleshooting and Debugging, etc.

This system of grooming isn’t labor intensive. I find myself splitting a note or heading not when it becomes hard to search (with global search, it’s never hard to find things), but rather when I start questioning where to put a new bullet point.

Benefits of Note Taking

Here are some results worth highlighting.

- In the beginning of 2017, a coworker showed me how to do something. I did it twice, wrote it down, and forgot about it. A year later, a new developer asked me the same question, and before I tried any code, Googled anything, or asked for any details, I was able to search a couple of words and sent them a line of code that would have taken either of us hours to figure out. As a bonus, I never needed to bug the coworker that had originally shown me.

- I started a new project in Java, which I used for years but have taken a five-year hiatus from. I recapped the major sections of the those notes; datatypes, tools, how to interface with a database, and the biggest things I’ve ever gotten stuck on. In less than a day, I was coding new features and it was like riding a bike.

- I sat down with a friend who showed me an AngularJS side project he is working on. I took some notes and found myself interviewing a candidate with an Angular background six months later. I knew what the candidate was talking about and how to ask questions from an AngularJS prospective.

- Throughout the day, I write down the task I’m on every time I switch to something new. This log becomes my standup notes, which is helpful day to day but even more helpful on teams that only meet once per week. The log is also useful in coming up with a recap of the quarter or creating slides for presentations about features my team has built.

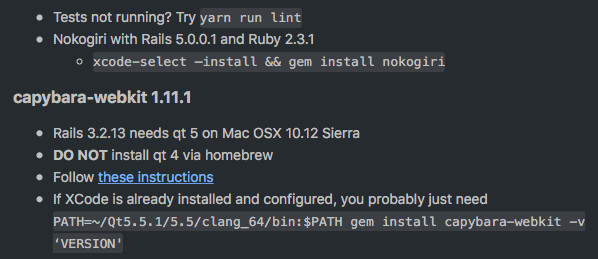

Here’s the biggest benefit, the one that has saved me days of time: logging issues I run into. Don’t worry, it’s not labor intensive either. As soon as you run into an error that’s harder to figure out than finding the solution as the first result on Google or StackOverflow, copy and paste it into your note for that topic. Whether you spend two minutes or two days debugging it, write the best description possible of the cause and the shortest list of commands possible to resolve it. Same flow of organization; if bullets get long, turn it into a heading.

Real issues and solutions from various frameworks

There’s no better feeling than running into an obscure error message you had months ago and copy/pasting a command that saves you hours of looking at articles that you know you’ve read before.

A Note on Note Taking

Notes need to be in your own words; that’s what makes them searchable and useful to you. You call it a function, I call it a method. You search bash, I search shell. You organize by project, I organize by language. A good technique I’ve found is to write a few names for something so that you can search it easier. For example, “Routes, Routing, Urls, Uris, Paths” as a heading instead of just one of those terms.

No need to take notes on things that turn up as the first google result. When learning something brand new, take notes on everything. But, when the basics are committed to long-term memory and are just taking up space, feel free to remove them. If you need to refresh on syntax, you can probably Google it and you don’t need to rewrite the docs. If you bring down production, however, probably worth noting what not to do next time. And although I have many project notes specific to my understanding, I still make an effort to keep any public-facing notes up to date, such as project Readmes and documentation.

Additional Tools and Tricks

Quiver notes are easy to hack on since they’re all JSON content and metadata files in folders that map to your notebooks. Using the todo list app, Wunderlist, which has a very simple API, I wrote a script for my packing checklist for traveling. It grabs my packing checklist from Quiver and exports it Wunderlist, which I then alias in my zshrc. When I go on a trip, I type pack into terminal and I have a packing checklist on my phone. Every time I forget things, I add to the note list in Quiver so I don’t forget next time.

I hope you’ve learned a thing or two about the benefits and how-to of developing your external brain. Taking notes is something I didn’t do much of in my youth, but it is a practice that I wish I started early on. Come up with a system of organization that maps how you think of things, make the growth and grooming of notes organic rather than a hassle, and harness your external brain. It’s a powerful tool.

Be sure to follow @doximity_tech if you'd like to be notified about new blog posts.